Idea Generation: How a business class is designing better futures for girls school 8,400 miles away

Published: February 24, 2021 / Author: Carol Elliott

Kalongo, Uganda

Kalongo seems a moonshot away from the University of Notre Dame. Located in the impoverished northern region of Uganda, the urban center with a population of about 15,000 offers limited options for young women coming of age in the country’s patriarchal society, where the power grid is unreliable and the average income is roughly a dollar a day.

Added to those conditions, Kalongo is shadowed by a tragic legacy. In the 1980s, the ultra-violent rebel group the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) abducted as many as 30,000 child victims to serve as soldiers and sex slaves. Most escaped or were released in the years between 2003 and 2006. Very few had homes or families to return to, and were often rejected by any surviving members if they did.

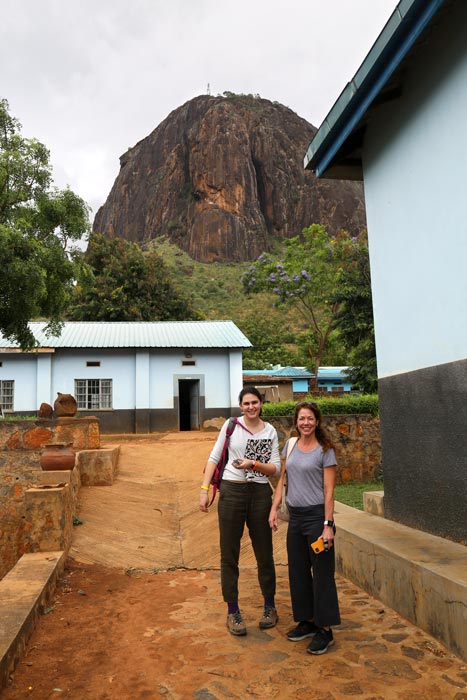

Design-thinking team arrives at Kalongo, Uganda. (Photo by Aubrey Flagler)

In early March 2020, a group of 10 Notre Dame students and their professor arrived in Kalongo, just ahead of the COVID-19-related travel shut down. They, along with 60 classmates back on campus, were part of the undergraduate Innovation and Design Thinking class taught by Wendy Angst, a teaching professor at the University of Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business and a fellow with the University’s Pulte Institute for Global Development.

In the months leading up to their visit, the students devoted countless hours researching, re-envisioning and reimagining a path forward for these young women through the work of school founded just for this purpose — the St. Bakhita’s Vocational Training Center (SBVTC).

Angst is a firm believer in the importance of experiential learning. She referenced a quote from Confucius: “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.” In past years, her students have applied their design thinking skills to real-world business problems for companies including the Disney Channel, LiveNation and Hearst Communications.

Entrance to the St. Bakhita’s Vocational Training Center

Three years ago, an anonymous donor endowed experiential learning for Angst’s classes. When St. Bakhita’s became the project focus in spring 2020, the donors offered additional support for students to have an opportunity to implement and test their ideas to have meaningful and long-lasting impact. This support has enabled Angst to look at a multi-year commitment to work with St. Bakhita’s.

There are a number of ways to think about the work of the Innovation and Design Thinking class with the training center. It’s a learning experience for the students; an innovative approach to addressing societal issues; and an example of an extensive collaborative effort between the center, the University, aid agencies, and a number of extraordinary individuals.

And at the very heart of it, the project is also about iteration, a word that simply means do-over. It’s the core concept of the design thinking model that the students applied to finding solutions for these young women. And it’s the core belief underlying the St. Bakhita’s project — that every life has infinite possibilities to start again.

A DARK PAST REVISITED

To understand what brought the Notre Dame team to Uganda and what is at stake for St. Bakhita’s involves revisiting that very dark chapter of Uganda’s history. The withdrawal of the LRA left a shattered land. The government devised various plans to shelter the newly released child victims until family members could claim them. But in reality, few were ever claimed and reunited, which left thousands to dire fates with little hope for the future.

In 2007, St. Bakhita’s Vocational Training Center was founded by an Italian organization to support and educate the ex-abductees with plans to teach skills in computer studies, secretarial studies, catering and tailoring. Fittingly, the school is named after female Sudanese slave turned St., Giuseppine Bakhita, the patron St. of human trafficking survivors. More than a thousand students have participated in SBVTC programs, with about 800 graduates.

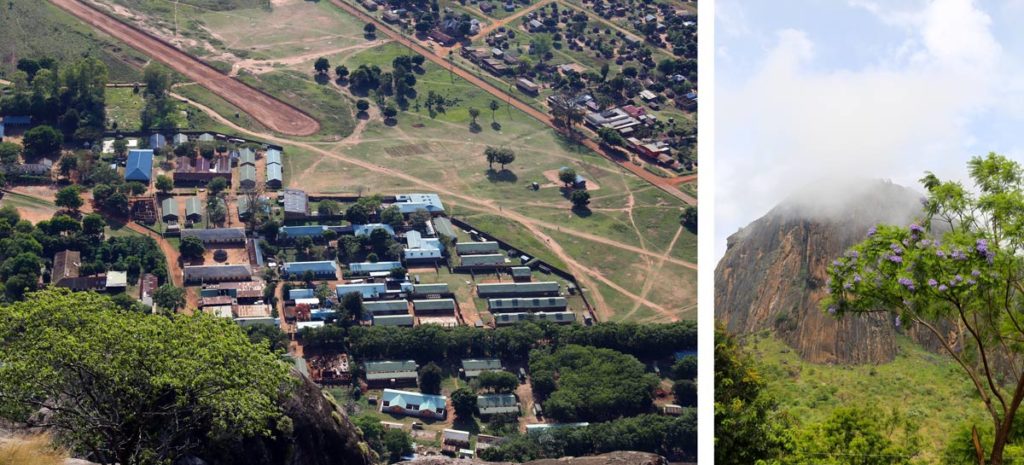

Mount Oret, Kalongo, Uganda (Photo by Bruce Morris)

Schools like St. Bakhita’s provide girls a path to self-sufficiency by providing marketable job skills. However, tuition is a struggle for many. While St. Bakhita’s has capacity for over 200 students, only 30 are enrolled and only 10 were present during the team’s visit. “Most students are not able to begin their studies at the start of the school year,” Angst explained. “The students arrive as the families scrape together enough money to cover the costs of tuition.”

In photos, the school is an unprepossessing concrete building situated on a compound with a few smaller outbuildings nearby. Spirals of razor wire top a 10-foot wall to the front of the school. The wall, the yard and the surrounding landscape are stained with the dark orange color of the soil. A tractor, worn and rusted but usable, sits in the yard. About six miles away sits a 375-acre farm, which would prove to be a major part of the ultimate solution proposed by Angst and her students. Mount Oret, a solid granite formation considered a challenging peak for climbers, hovers as a backdrop.

ND students get the lay of the land at St. Bakhita’s. (Photo by Aubrey Flagler)

Bruce Morris recalled having his expectations “slightly shattered” upon arriving at the school. “Throughout the semester, we had interviewed graduates from St. Bakhita’s, and from their anecdotes, I had pieced together an idea of St. Bakhita’s having a modest, yet bustling operation, capable of supporting tens, if not hundreds, of students,” said Morris, who graduated from Notre Dame in May. “However, when we arrived, we quickly realized St. Bakhita’s had declined since the ‘glory days’ of the school’s first cohort of graduates. Only 10 of the expected 30 students were in attendance and despite having over 30 pieces of tailoring equipment, only two were operational.”

A vivid example of what is at stake was illustrated to the students by a set of 16-year-old twins — “Mary” and “Elizabeth.” One of 10 children, Elizabeth was able to attend SBVTC by raising money for tuition by growing cassava and maize in her family’s garden. Even more critically, her aunt acted as an advocate for her to go to the school, where she studies tailoring. Otherwise, it’s likely that the family would prioritize keeping her at home to help with subsistence farming and childcare.

But her twin wasn’t as fortunate. She was married off to a 38-year-old man for the dowry.

“And it just happened that while we were at the school, the night before we left, Elizabeth’s sister came to visit,” said Angst. “Elizabeth hadn’t seen her since the wedding. Her sister was now eight months pregnant. It was just heart-wrenching to think about the very different futures that lay ahead for these girls.”

START WITH EMPATHY

Traditional humanitarian efforts in situations like this might call for aid, but here’s where the design thinking approach is decidedly different. Design thinking begins with putting yourself in the shoes of the user to live the problem from the user’s perspective. The focus is to think about a problem through a holistic and flexible process focused on empathy for those you are seeking to serve, to ensure the creation of a human-centered solution.

Kalongo, Uganda (Photo by Bruce Morris)

Because it is necessarily a collaborative approach, design thinking is often considered an effective way to tackle complex socio-economic problems such as health care and education that do not have straightforward answers.

The approach typically involves five steps: empathize, define, ideate, prototype and test. These translate into developing an understanding of the human needs at the center of the problem or challenge; reframing the problem in human-centric terms, generating a lot of ideas for possible solutions, and developing and testing prototypes in an iterative fashion. At every step, the design thinkers make alterations and refinements to the innovations in order to keep driving toward the solution that best meets the current and future needs of the user. It’s a hands-on approach that encourages a deep level of trust in the process and an aptitude for creative problem solving.

It’s important to note, said Angst, that the process begins with empathy.

For the Notre Dame team, this means a tremendous amount of work was done before the students landed in Uganda.

“Before we even went in-country, we spoke to numerous experts from different nonprofits and schools at Notre Dame and around the world,” she said. “We also had a Ugandan Notre Dame doctoral student join every class as an adviser to the teams, and we worked with a dedicated adviser on the ground in Uganda to help with coordinating interviews.”

Every member of the class conducted an “immersion,” or mini experience intended to give the students perspective into a particular aspect of the problem. “For example, we learned that students in Uganda will go three days a week on average without having electricity for 10 hours a day,” said Angst. “We had students complete an immersion to see what it was like to live without access to electricity for 10 hours while still carrying out their studies.”

ND students consult with experts. (Photo by Aubrey Flagler)

Since St. Bakhita’s has the potential for developing the nearby farmland, other students visited South Bend’s community Unity Gardens to experience combining farming as part of their education. The students also interviewed 60 former SBVTC students — the young women who had been LRA victims.

The spring break trip provided a chance to build on their understanding of the realities facing the school and its students and to experience the school and the environment firsthand. The students focused on six strategic projects related to curriculum, revenue generation, resource development and skills training. As part of their in-country research, they sat in on classes at St. Bakhita, visited the farm affiliated with the school, met Ugandan entrepreneurs and toured other vocational programs. They also took time to get to know the SBVTC teenagers.

ND students examine a solar panel on a roof at St. Bakhita’s. (Photo by Phuong Le)

Being in-country, Angst says, was eye opening. For instance, their trip to the farm quickly reset their assumptions about the agricultural setting in Uganda. “We pictured a farm like you would see here in the U.S.” Angst says. “But the farmland was not cultivated as you would expect.” The fields were not plowed, the solar-powered well wasn’t running because its solar panels had been stolen, there were no livestock, and the shea trees, known for the high value of the nuts it produces, grew wild and were not harvested and processed in a timely fashion.

Sophia Kartsonas (MGT-Consulting ’21) was struck by the contrast between her and Elizabeth. “When I was 16, I was a junior in high school and the biggest cause of stress in my life was over if I would pass my driver’s test,” she says. Meanwhile, Elizabeth worries about whether she’ll be able to find a job and send money back home to her family and if her younger sisters will have the same fate as her twin.

But the experience also worked in the opposite direction, with students deeply impressed by how much they shared. “There are strong differences that characterize our underlying cultures, but after being in Uganda it’s easy to see far more similarities,” said Aubrey Flagler (MGT-Consulting ’20). “We met bright and determined women fighting for reforestation, an altruistic principal focused on creating a self-sustaining academic institution, and many girls seeking better futures through education. Without being there in person to meet each of these people and see their world alongside them, we would not have been able to design for St. Bakhita’s with true awareness and empathy.”

TREES

Shortly after the students returned to campus, all Notre Dame classes transitioned to online teaching due to COVID-19. Working virtually, the Innovation and Design Thinking students moved to the next steps of the process by “ideating” ways to improve the lives of the “Elizabeths” and the “Marys.”

Farmland in Kalongo, Uganda. (Photo by Kendyl Pettit)

This is another point where a distinction emerges between a design thinking approach to development and a traditional one. The traditional approach might have focused on providing aid for scholarships or improving the school’s facilities. The design thinking team took a holistic view to consider the broader societal challenges and the overlooked potential resources available.

The solutions extended beyond St. Bakhita’s primary mission to provide young women with opportunities to learn employable skills. They also considered how to improve access to healthy foods and ways to support affordable and environmentally responsible alternatives for families to meet their energy needs. As it happens, Uganda is in the midst of a massive deforestation crisis. More than 86% of households depend on the burning of charcoal and wood as their energy source, which has led to the destruction of more than 60% of its forests.

The Innovations and Design Thinking team saw the challenge as two-fold: 1) addressing the social and economic devastation left by the LRA, particularly the impact on young women, and 2) addressing Uganda’s growing deforestation crisis.

The proposal that emerged was the Teaching Reforestation & Entrepreneurial Empowerment at St. Bakhita’s or TREES Initiative. Centered on building a sustainable agri-business, the plan starts with establishing 50 “Innovation Acres” that will initially focus on planting a variety of fruit, avocado and charcoal trees. St. Bakhita’s students will learn the practical skills and value of agroforestry and environmental preservation and also become equipped with the entrepreneurial knowledge needed to harvest and sell these products. Work on the farm and the resulting revenues will be used to help offset tuition fees and expand the school.

In the process, St. Bakhita’s students will gain a sense of empowerment and learn practical skills such as how to open a bank account and manage money. In turn, they will be encouraged to take these skills and share them in their communities, becoming local change agents who create the inspirational foundation for Uganda’s new generation of female leaders. The initiative includes developing a support network for students and graduates, and longer-term support for entrepreneurial endeavors.

Utilizing a design-thinking approach, the team knows TREES has the potential to spark new, community-based ideas in Kalongo, if not northern Uganda as a whole. The traditional approach to problem solving might have yielded a one-dimensional, tried-and-true strategy of maximizing farm yield and revenues with staple crops and incremental farming innovations. However, with the insights generated throughout the design process, TREES not only achieves the results of traditional solutions by introducing and testing novel crops and farming techniques to the region, but has a system in place to empower the students with practical skills, stimulate new opportunities for organizational collaboration, and allows St. Bakhita’s to participate in future environmental preservation efforts.

A group of St. Bakhita’s students. (Photo by Wendy Angst)

COLLECTIVE EFFORTS

(Photo by Wendy Angst)

It’s important to note that at this point, the St. Bakhita’s project involved not just the Innovation and Design Thinking class, but an extensive and extraordinary collaboration. Advisors have included alumni affiliated with nonprofits working in Uganda and other Notre Dame students, both graduate and undergraduate, eager to support the creation of a successful program at St. Bakhita’s.

“The design thinking approach intentionally brings together teams comprised of individuals with diverse backgrounds to ensure that all sides of the challenge are considered,” said Angst. “We seek to bring together different disciplines and different experiences to work together and learn from one another.”

Notre Dame collaborators and advisers included the Pulte Institute, the Keough School, the Center for Social Concerns, the Alliance for Catholic Education and the Notre Dame MBA. Pulte Institute fellow Tom Loughran, a board member of nonprofit BOSCO Uganda which previously set up 14 computers at St. Bakhita’s, traveled with the team. Father Joe, the priest with the Archdiocese of Gulu which oversees the school, continues to help oversee the work on the ground in Uganda in collaboration with Jennifer Okusia, CEO of BOSCO Uganda.

Mendoza alum Matt Alverson, a partner with global innovation and design consultancy IA Collaborative and adjunct instructor for the Notre Dame Executive MBA program where he teaches Design Thinking for Business, frequently joins the weekly calls to help think through the challenges that arise.

Wendy Angst and one of the ND students at St. Bakhita’s. (Photo by Aubrey Flagler)

“Wendy is proving that not all credit hours are created equal,” explained Alverson. “First, she’s using experiential learning to teach students about the modern convergence of design thinking and business thinking. The methods they use for the St. Bakhita initiative are the same used by market innovators like Nike, Airbnb and Amazon. Second, she’s doing the hard work of combining learning with social impact . Father Sorin declared Notre Dame would be ‘a powerful force for good,’ and this work delivers on that vision.”

Frank Spesia, who holds Master of Education and Master of Global Affairs degrees from Notre Dame, also advises. Spesia currently works as a public health fellow with the St. Joseph County Department of Health. He has worked on education initiatives in Malawi and Chile, and his most recent project focused on identifying cost-effective methods of school improvement in under-resourced Chilean public schools.

Finance major Keian Gatewood (BBA ‘24), a beekeeper who founded the Bee Brand company, has also advised the team. He previously launched a beehive project in the Philippines and possibly can do the same for St. Bakhita, providing a potential export product and support for the pollination of trees.

Chris Udall (MBA ’21) took the graduate version of Angst’s class last fall, where the class worked with a Napa Valley winery. The St. Bakhita’s project, though, was more in line with his interests and long experience in establishing nonprofits focused on rescuing youth from recruitment by extremists and sex traffickers so he joined the independent study that Angst put together for fall semester for interested students.

“My main passion in life really is youth-centric economic development,” said Udall. So the fact that they’re working with young women that have gone through the civil war, that some of them are coming from this child soldier life, and bringing them into a space where they can learn that they can innovate a new life for themselves.”

Udall’s current effort, Rebuild for Peace, located in the Middle East, helps youth get out of ISIS and Hezbollah recruitment and puts them into vocational jobs in different fields that address skill gaps and market gaps. What he finds most compelling is the message that given a chance, even an individual who has suffered unspeakable tragedy can “reiterate” or rebuild a life.

“I always tell my students, ‘It’s not about learning carpentry or sewing or masonry,” he continued. “It’s about learning that you can take a raw material or something that’s broken and create something new out of it, or something useful and beautiful. And you can do the same thing with your life. Just like you learned this one skill, you can learn an infinite number of other skills and keep creating yourself as a person.’”

CATALYSTS FOR CHANGE

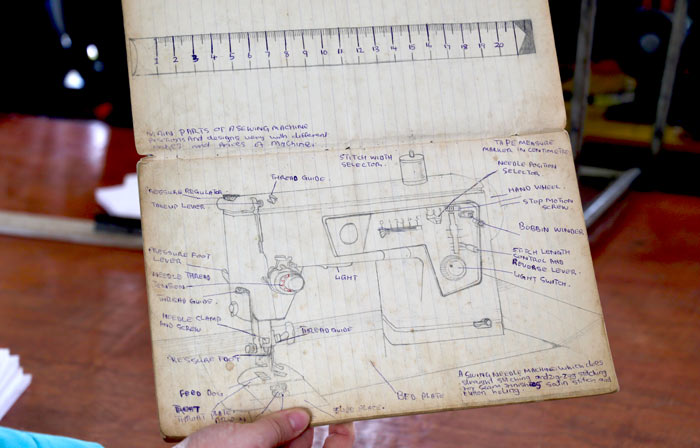

Sewing room at St. Bakhita’s. (Photo by Sophia Kartsonas)

When Angst’s class ended in May, COVID-19 continued to wreak havoc globally. In Uganda, the government had issued a national stay-at-home order mere weeks after the team’s visit. All SBVTC students were sent home immediately.

For Angst, this meant it was time to double down on their efforts. The pause granted the team the opportunity and time to “redefine the what, how and why of the school’s curriculum.”

During the summer, a team of students continued researching vocational schools in Uganda and abroad, determining best practices with regard to curriculum scope, tuition payment systems, teacher recruitment strategies, marketing, and post-employment activities. The research will inform decisions about the curriculum, specifically, how to best balance activities in the classroom and the field, and how to introduce entrepreneurship into the students’ lives and the community at large.

They also hope to discover ways to expand the career paths available beyond the legacy coursework in tailoring and catering. Some of the ways that the team currently reimagining vocational education include adding training in agroforestry and reforestation. A state-of-the art computer lab also is currently being installed with support from the endowment family and Dell computers.

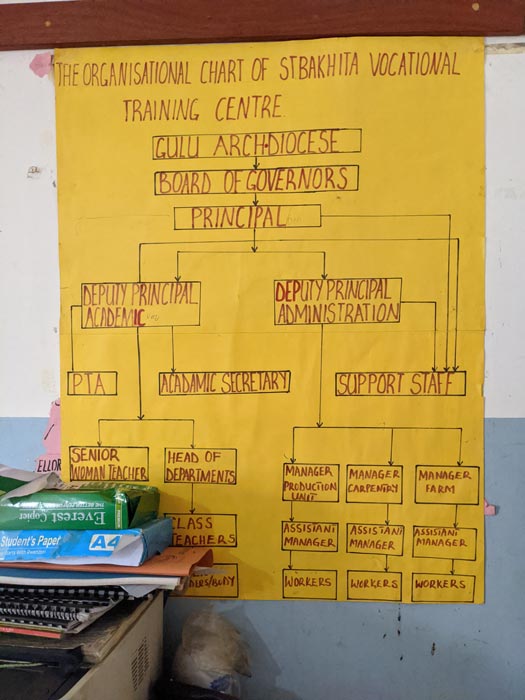

Organization chart. (Photo by Wendy Angst)

This past fall, the Design Thinking team stayed busy. They built a new website for the school and developed a program for partial tuition scholarships. They received approval to launch a Notre Dame club, Innovation for Impact, to include other Notre Dame students in advancing the work beyond the classroom and to provide pathways for the Notre Dame community to engage in fundraising and partnerships for SBVTC. They launched a GoFundMe campaign that has raised about $44,000 to date in additional funds to help support TREES initiative.

Perhaps most critically, after discussions with BOSCO Uganda, they realized the importance of establishing in-country leadership at St. Bakhita’s charged with carrying out the various objectives. This includes hiring at minimum a farm manager, a financial manager, a project manager and a school principal.

In December, Angst was in the process of finalizing the hiring of Victoria Nyanjura, a 2020 graduate of the Keough School’s Master of Global Development program, to serve as a technical advisor at St. Bakhitas. Nyanjura was herself kidnapped by the Lord’s Resistance Army from her school in 1996 and held hostage for eight years, suffering brutal beatings and rape before eventually escaping.

Nyanjura went on to found a number of organizations and initiatives that support and protect women and children in crisis regions, including Women in Action for Women. She is one of the Founding members of the Leadership Council for the Global Survivor Network. In 2019, Nyanjura received Amnesty International’s Ginetta Sagan Award for Women’s and Children’s Rights. (Read more about Nyanjura’s story in Notre Dame Magazine’s “Eight Years a Captive.”

MUCH NEED, EVEN MORE OPPORTUNITY

(Photo by Wendy Angst)

As the difficult fall 2020 semester drew to a close, Angst reflected with deep appreciation for the work of the Innovation and Design Thinking students, the benefactor and the many others who devoted time and energy to the St. Bakhita’s project. She mentioned the grit of the team that traveled to Uganda during the uncertain spring, staying in a hotel under mosquito nets with limited access to electricity and cold-water showers.

She returned to a statement that serves as a theme for the class: Not all credit hours are created equal.

“In other experiential classes I have taught in the past, we get to the point where the students come up with really phenomenal recommendations, but then the semester ends. We leave the recommendations with the client and move on,” she said. “But here we made the commitment that this would be our project focus for the next three to five years, to enable meaningful impact through implementation of student initiatives.”

For Alice Bruemmer (BS ‘20), who earned a minor in Innovation and Entrepreneurship and also traveled to Uganda in spring 2020, the Innovation and Design course brought to life the expression “learn by doing,” which extends far beyond the classroom.

“We saw firsthand the town of Kalongo, the energy of the SBVTC students and the possibilities for the project that lay before us,” said Bruemmer, who spent the summer and fall working as a land management assistant crew leader at the Tahoe Resource Conservation District in California. “Inspired by my experience in the class and motivated by the good I hope to do, I have continued this work after graduation, as a member of a small team of invested individuals. We are so excited about the future of SBVTC and its reforestation initiative that is set to begin in March 2021.”

Morris, whose expectations were initially shattered, found great possibilities and even beauty in Kalongo. He also has continued to work on the project even after he graduated.

St. Bakhita students. (Photo by Aubrey Flagler)

“At times, the situations we strive to improve appear hopeless, especially when tangled in a complex web of social structures built to maintain a hierarchical status quo,” said Morris. “However, individuals like those we encountered are proof that beneath the surface of struggle exists small, but powerful, catalysts of positive change. Such passion provides me with hope for not only the future of our class’s solutions, but my own future journey into social entrepreneurship post-graduation.”

The next class of Innovation & Design students will begin their work with St. Bakhita’s in spring 2021. Each Notre Dame student will be assigned a SBVTC student to work with directly throughout the semester. The new cohort of SBVTC students have been designated as the “Innovation Scholars” with the expectation that they will work closely with their ND counterpart to collaborate, iterate and prototype a reimagined future for best-in-class vocational education.

“And as you might imagine, working with a school like St. Bakhita’s involves your full heart and mind,” said Angst. “There is so much need, but even more opportunity. The opportunity to take our classroom across the world to work with these incredibly strong and resilient girls. The opportunity to collaborate with partners here and around the world. The opportunity to learn by doing. The opportunity to make a difference. To me, this embodies what it means to be a part of this amazing Notre Dame community.”