Man on a Mission

Motivated by decades of military and government work, Kevin Graham is using his experience to save those most vulnerable to human trafficking through his nonprofit, The Village Mission.

Published: August 30, 2022 / Author: Katie Rose Quandt

Kevin Graham (EMBA ‘21) was sitting on the patio of Rohr’s at the Morris Inn in June 2022, casually catching up with a few of his fellow grads, when he was asked about his passion project: helping at-risk people (including some he knew from his time in the military) escape the Taliban and resettle out of Afghanistan.

Up until this point, Graham and his wife Joanna had invested significantly in the effort. But as those funds ran low, they were in desperate need to find new sources of funding to enable his project to really make an impact.

Kevin Graham with wife Joanna and son.

“It was this amazing moment, on the patio there,” Graham recalled. After filling in his classmates, “They were like, ‘Kevin, it’s day one of electives week here at Mendoza. Let’s create a nonprofit.’”

Less than a month later, he had established The Village Mission as a corporation and assembled a board of directors, including several members of his Executive MBA cohort. Now, just two months after that, and inspired by that chance conversation with his friends, The Village Mission is fully launched and partnered with a fiscal sponsor while awaiting the government’s 501(c)(3) status approval.

The Village Mission will help human trafficking victims and those at risk of being trafficked escape dangerous situations, and provide support and resources as they reclaim their lives and settle in a new country. Graham expects the work to expand to a number of countries, including in Europe and Africa. Back in the United States, the nonprofit also will train and educate hotels and businesses to identify the signs of trafficking and to avoid “unwittingly becoming a safe haven for human trafficking activities.”

Graham first witnessed disturbing signs of human trafficking while stationed overseas during his eight years as an active duty Marine, followed by 14 years as a civilian within the special forces and intelligence communities. During those years, he was frequently deployed, operating on the ground to coordinate and support “the folks who jump out of planes” as they carried out clandestine rescue operations and other missions.

This meant he spent a lot of time working from hotels in what he described as “seedy” areas of foreign cities. “I was exposed to a lot of human trafficking, happening more or less in front of my eyes, that I couldn’t do anything about. If I had tried to interfere with it, I would have blown my cover and jeopardized the mission that I was there to do,” he explained.

“And so after a while, as you can imagine, I carried around a considerable weight on my shoulders. From seeing some obvious trafficking situations, including with young girls or young boys, but not being able to do anything about it.”

Human trafficking is one of the world’s fastest growing criminal enterprises. The International Labour Organization estimates that on a given day, 40 million people around the world are victims of trafficking, which can take many forms including forced labor, sexual exploitation, child soldiering, forced marriage and domestic servitude.

In September 2018, after 22 years working with the armed forces, Graham started a new career that would keep him closer to his wife, one-year-old son and their home outside Washington, D.C. But he couldn’t forget what he had seen.

When he struggled with the transition and his wife suggested finding a passion project, Graham’s mind went back to human trafficking. He created a business plan for a company that would train and educate U.S. businesses on how to spot signs of trafficking. Unfortunately, the arrival of COVID-19 in 2020 stressed the hospitality industry nearly to its breaking point, putting his plan on hiatus.

Then, in the summer of 2021, Graham’s attention turned back to Afghanistan. The Taliban had returned to power, brutally targeting journalists, former government officials and activists; obliterating women’s rights; and attacking and killing people belonging to ethnic and religious minorities. Graham feared for many of the people he had collaborated with throughout his years in the military. “I reached out to them and said, ‘Hey, are you okay?’” he recalled. “‘Are you safe? Do you have a way out? What can I do to help?’”

Then, in the summer of 2021, Graham’s attention turned back to Afghanistan. The Taliban had returned to power, brutally targeting journalists, former government officials and activists; obliterating women’s rights; and attacking and killing people belonging to ethnic and religious minorities. Graham feared for many of the people he had collaborated with throughout his years in the military. “I reached out to them and said, ‘Hey, are you okay?’” he recalled. “‘Are you safe? Do you have a way out? What can I do to help?’”

Graham collaborated with a network of friends and former military contacts to help more than 300 people evacuate out of the airport in Kabul that August. But when the gates closed, many remained behind. He continues to work with his networks to help persecuted people and families escape dangerous situations in Afghanistan, via a network of safe houses. “That’s kind of taken over the past year for me,” he said.

Graham often finds people to help through word-of-mouth. A teacher at his son’s school, who had herself fled the Taliban in 2004, told him that her brother and sister and their families were desperate to get out of Afghanistan. The family members included Afghan military, a former civil servant, a journalist and a woman who owned an art studio. These careers, combined with the fact that they are Hazara, a severely persecuted ethnic minority, put their families in danger of death and human trafficking.

“Her brother’s got a young daughter who is very vulnerable to being wrapped up in human trafficking with the Taliban,” said Graham. “He’s got a son also, who has almost been taken a couple of times into child soldiering to forcibly join the Taliban.”

“For the past year, I’ve been moving them from safe house to safe house, using existing networks that I have there on the ground,” he explained, “while we work through the legal process of trying to get them some humanitarian visas to actually come here and live with the sister.”

Of the 19 people Graham has been working to evacuate over the past year, 14 are now in hiding in Pakistan, with plans to eventually move on to Turkey. The situation is intense and dangerous for the families and those helping on the ground. One of the women gave birth while in hiding in Pakistan.

“It was a whole operation of paying off doctors, and people opening back doors of the hospital, and giving birth in a back room, and then being back in a safe house that night so she wouldn’t get discovered because she was undocumented,” said Graham. “It’s been an absolute roller coaster.”

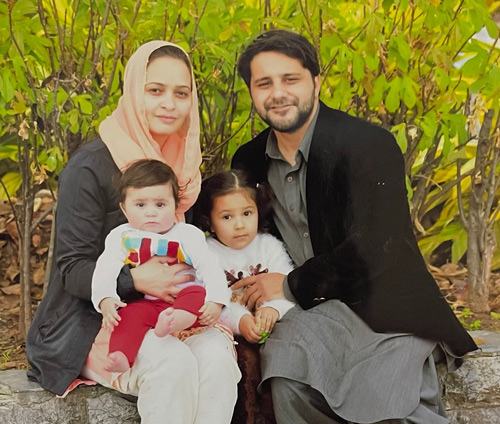

Family helped by the Village Mission

There is no shortage of people for The Village Mission to help. “In the D.C. area, we’re in such an international community,” he said. “With the word getting out, we have lots of people that will say, ‘Hey, listen, I have a sister, or a cousin, or my parents, and they’re worried about their kid being kidnapped for child soldiering.’”

He has also had generous offers from law firms to help with pro bono immigration work. “We don’t even know if the U.S. is the final destination for some of these people, but they just need to get out of where they are,” he said.

So far, Graham has funded the work by piecing together his own savings, pro bono support and financial help from friends. But, as he explained to his classmates at Notre Dame this summer, he was running out of funding.

By the time he had that conversation, Graham had been passionate about preventing human trafficking for decades. He had on-the-ground networks in foreign countries, and experience coordinating complicated rescue missions. He was sitting on his earlier business plan and all his research into trafficking prevention.

And as was clear that night, Graham’s business degree at Notre Dame was the missing piece of the puzzle, providing the tools, contacts and that push from his friends to turn his scrappy rescue team into The Village Mission.

“There was kind of this magic moment where we were all looking at each other,” he recalled. “Like, ‘My gosh, man, talk about growing the good in business. Let’s do it.’ And we did.”

“This is me paying a little bit of penance for all those years of not being able to do anything, and seeing all these horrible things happen,” said Graham. “And now, I’m in a position where I can do something, and I can do it all from home.

“And so this is a way that I can still do good, and still be here as a father and a husband. And be a good example for my son, that sometimes there are things that are bigger than you, that you’ve got to step up and do. Because no one else will if you don’t.”

Related Stories