Investors overvalue companies that align with presidential policies – and their mistakes leave money on the table

Published: May 19, 2023 / Author: Ty Burke

Republican politicians typically favor low taxes and less regulation, which seems like a recipe for corporate profits and stock market success. In reality, however, this is not what happens.

Stock markets deliver higher returns during Democratic presidencies than Republican ones, and that has held true for many decades. It’s a counterintuitive finding known as the Presidential Puzzle, but the observation applies to the market as a whole.

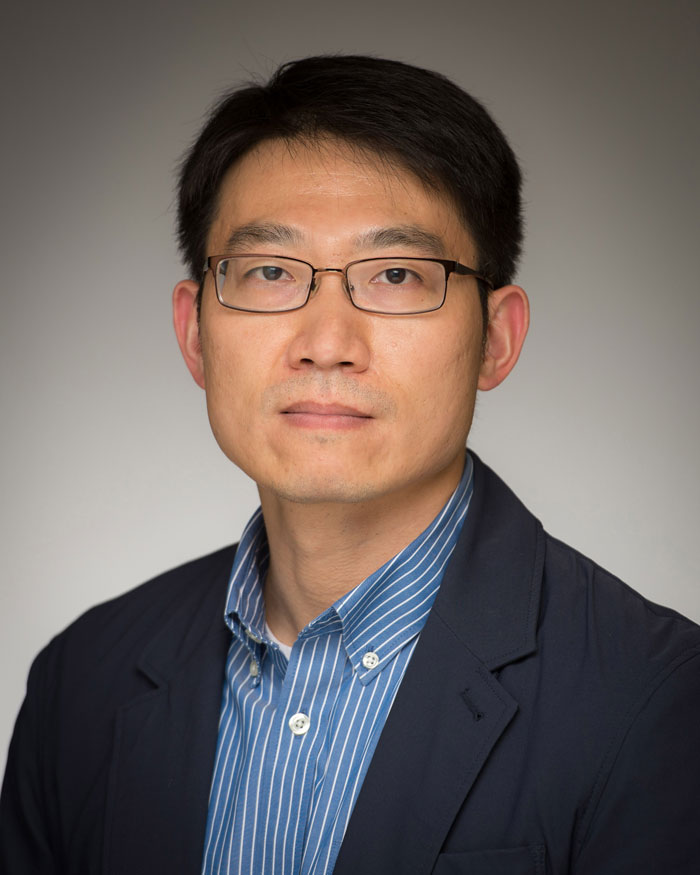

Zhi Da

Finance researcher Zhi Da wanted to understand more about how presidential politics affects the performance of individual stocks, especially those that could benefit from a president’s policies – or be hurt by them.

“Presidential politics affect markets, and any time there is a Democratic president, returns are going to be hot going forward,” said Da, the Howard J. and Geraldine F. Korth Professor of Finance at the University of Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business. Da’s recent research, “Presidential economic approval rating and the cross-section of stock returns,” examined the performance of individual stocks over a 40-year period.

Every president has a policy agenda, and some companies will be more aligned with it than others. Da wanted to understand how this affected a stock’s price and eventual returns. He found that companies aligned with a sitting president’s policy agenda did have an initial price bump, but it didn’t last.

When investors observe that a company is aligned with the president’s policies, they buy its stock, pushing its price higher. Yet over a one-year horizon, Da found that companies not aligned with presidential policies actually delivered better returns. He argues that this is because investors overvalue the benefits of policy alignment, and push prices higher than the company’s actual value. But eventually, investors come to terms with their mistakes, and prices come back to earth.

The study, published in the Journal of Financial Economics, was co-authored by Zilin Chen of the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Dashan Huang of Singapore Management University and Liyao Wang of Hong Kong Baptist University. The researchers built an index of the public approval ratings of the president’s handling of the economy between 1981 and 2019. This drew from more than 2,100 polls on economic approval conducted by multiple different polling agents, including Gallup, The New York Times and NBC News/The Wall Street Journal. They called it the presidential economic approval rating index or PEAR for short.

To measure the performance of individual stocks against the index, Da adapted the financial concept of a stock’s beta. When markets move, not all stocks increase or decrease by the same amount. A stock’s beta quantifies its volatility relative to the overall market. It is a statistical calculation that gives the overall market a value of 1.0. A stock with a beta greater than 1.0 is expected to move more than the overall market; a stock with a beta less than 1.0 is expected to move less.

For this research, Da created the measure of PEAR beta, which adapts the concept to measure stock volatility relative to the president’s economic approval rating. A stock with a high PEAR beta goes up more than the overall market when the president’s economic approval rating is high. A stock with a low PEAR beta goes up less.

Consider the case of two energy companies during a time of transition. Renewable Energy Group (NASDAQ: REGI) is a biodiesel firm and New Concept Energy (NYSE: GBR) is a traditional energy firm in the oil and gas sector.

“During the presidency of Barack Obama, the stock price of the clean energy firm outperformed the market, while the oil and gas firm did not. This is because when Obama’s policies were popular, there was a perception this will benefit clean energy firms. And that new regulations could hurt more heavily polluting traditional energy firms,” said Da.

Under the Obama presidency, Renewable Energy Group had a high PEAR beta premium. But despite this apparent tailwind, the company earned lower returns than New Concept Energy. Da called this the low PEAR beta premium.

“This was caused by mispricing on the part of investors. When investors feel firms will do well, they price their stock too high. But when earnings are announced, they have made less money than they expected. They trade out of the stock and its price goes down,” said Da.

“We found analysts are too optimistic about high PEAR beta firms. Sometimes people get too excited, and there are not enough rational investors in the market to correct the overpricing. Investors need to face the reality of an earnings report before they admit their mistake. Eventually, they face reality and revise their expectations, but it takes up to a year.”

For low PEAR beta firms, it’s the opposite story.

“Traditional energy firms didn’t do well during the Obama administration, but when earnings came in, investors realized that they delivered pretty nice earnings. And because they make money, prices increase,” said Da.

In an illustration of the connection between the presidency and investor sentiment, the PEAR betas of these two energy stocks converged when Donald Trump was elected president in 2016. Eventually their PEAR betas reversed, and New Concept Energy’s stock price got a bump from its perceived alignment with the Trump administration’s affinity for fossil fuels.

The contrast in energy policy between political parties makes this sector a particularly neat illustration of the concept. But the effect was observed in the wider market through an analysis of a cross-section of monthly stock returns that used data maintained by the Center for Research in Security Prices. On average, stocks with a low PEAR beta premium earned 1% higher returns per month.

The effect could also be observed in major economies with strong trading ties to the United States, including Canada, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom. Da argues that these findings reveal a market inefficiency that could be leveraged by portfolio managers.

“Taking a practical point of view, we can identify a group of stocks with less risk, that outperform and have higher returns,” said Da.

“You are systematically taking advantage of money left on the table by investors whose decisions are mostly driven by politics. They are essentially leaving money on the table, and you could pick it up.”

Zhi Da’s research focuses on empirical asset pricing and investment. In recent papers, he studied the returns on financial assets surrounding liquidity events, cash flow risks of financial assets, equity analyst forecasts, and the mutual fund performance. He was a finalist for the Lehman Brothers Fellowship for Research Excellence in Finance (2005) and received competitive research grants from Moody’s KMV and Morgan Stanley. He teaches an elective course on debt instruments.

Related Stories